OXFORD-BURGHLEY ‘Pregnancy Letters’, CARDANO, Codes, Southampton (Henry)

Anno Domini, 1576

Up to the year 1575, Edward de Vere’s life (relative to many people at the time), was a charmed one. Although his father, John de Vere, the 16th Earl of Oxford, died in 1562, when Edward was twelve years old, Edward became, at the time of his father’s death: the 17th Earl of Oxenforde, Lorde Greate Chamberleyne of Englande, Viscount Bulbecke, and Lorde of Badlesmere and Scales. He inherited enormous wealth, including several hundred castles and accompanying properties, all of which, however, were to be held in trust for him until he became of age. Until his father’s death, he was tutored by Sir Thomas Smith, one of the foremost educators of the time, was enrolled in Queen’s College, Cambridge at the age of nine, and later matriculated at St. John’s college, Cambridge. In 1562, he was made a ward of the court, and resided in the household of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, chief advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. In addition to being arguably the most powerful man in England, Cecil was also twice Secretary of State, as well as Lord High Treasurer. De Vere was tutored by Laurence Nowell, the foremost Anglo-Saxon scholar of the day (and possessed the only known copy of Beowulf).

Edward was also awarded two honorary Master of Arts degrees, one from Cambridge, and another from Oxford. At the age of 17, he entered Gray’s Inn and studied law. At the age of 21, he married Anne Cecil, William Cecil’s daughter, was considered one of the best at tilts (jousting) in England, had various scholarly works dedicated to him, and was, for awhile, seen as one of Elizabeth’s favorites at Court. Before he was twenty six, he was publicly known as brilliant, a flashy if not outrageous dresser, a spendthrift, womanizer, riotous liver, horseman, an all-around champion at tournaments, highly skilled jouster, athlete, and published poet. He was fluent in several languages. It has been alleged he wrote plays, and is on record as being the best for comedy (although none of these plays have survived) as well as a sponsor and patron of the arts. From all contemporary accounts, he was a highly skilled and successful social animal. From all outward appearances and accounts, Edward de Vere’s behavior was the very definition of what we today would call that of an extrovert.

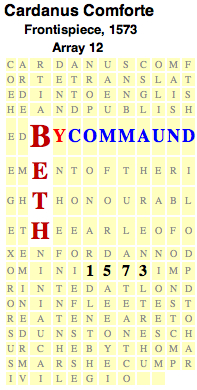

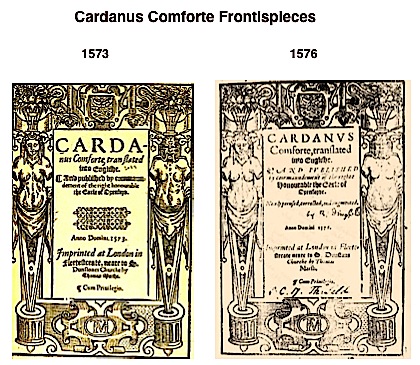

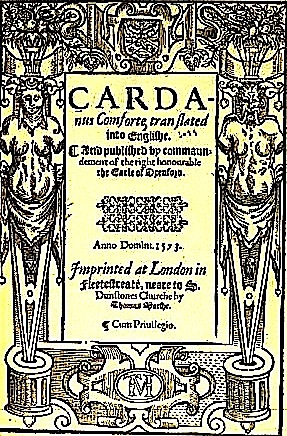

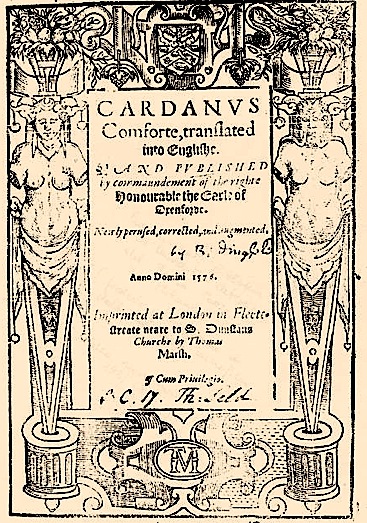

As we shall see later in more depth, de Vere’s social skills were harvested by the Crown for use in a much more private sphere. It is noteworthy that a work was published in 1573 by order of “the right honourable the Earle of Oxenforde.” Although the frontispiece to the work (see Fig. 1) gives no up-front attribution on the face of it (nor does the 1576 frontispiece), the Italian author was Girolamo Cardano, also known as Jerome Cardan, or simply Cardano. Cardano’s work was translated from Latin (De consolatione libri tres) by Thomas Bedingfield, who was one of the Gentlemen Pensioners who served Elizabeth I at Court.

Earl de Vere thought a great deal of Bedingfield’s translation, and wrote a 26-line dedicatory poem entitled: “The Earle of Oxenforde, To the Reader” with the first line, “The labouring man, that tilles the fertile soyle, . . . ” However, before dealing with de Vere’s dedicatory poem, a closer look at the 1573 frontispiece is in order.

Girolamo Cardano

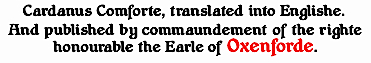

Written out as a single paragraph, the 1573 frontispiece says: “Cardanus Comforte, translated into Englishe. And published by commaundement of the right honourable the Earle of Oxenford. Anno Domini. 1573. Imprinted at London in Fleetestreate, neare to S. Dunstones Churche by Thomas Marshe. Cum Privilegio.”

When I first saw this frontispiece, I was drawn to several curious features. First of all, the first edition of this book was printed in Latin in 1542. As mentioned above, the original title was De consolatione libri tres. The author, Girolamo Cardano was a physician, astrologer, philosopher, brilliant mathematician, and compulsive gambler. However, his name is not mentioned on the frontispiece, nor is the name of Thomas Bedingfield, the translator of the work into English. The only name printed on the frontispiece is that of de Vere. The first printing states the publication is by order of the Earl of Oxenford, but ends with the Latin words, “Cum Privilegio”, a printing legal term loosely meaning” with permission” or “by the authority of “.

To a modern reader, this term would draw no attention whatsoever. However, getting permission for the publication of any book was a Crown mandate, decreed so by Mary I after the restoration of Roman Catholicism by her in 1555. In 1556, Mary charted the Stationer’s Company that gave members of the printer’s guild monopoly rights for any books they published. All books were required to be registered and approved by the Crown. Failing to do so was serious and meant certain punishment by the Star Chamber, a powerful group with vague jurisdiction, but having definite authority to execute severe punishment to those considered a threat to the Crown. Mary wished to have tighter control with respect to censorship. The point, here, is that the “Cum Privilegio” of any printed material was essential to have. How, then, was Edward de Vere in a position of authority to grant permission for a book to be printed in 1573 when Elizabeth I was ostensibly in control of what was printed? Elizabeth’s reign was arguably one of the strongest dictatorships, to date, in the English speaking world. I will address all the above issues in more detail momentarily. In short, then, where did the Earl’s authority come from, or from whom did it come? His name on the frontispiece directly states the printing of the book was by “commaundement”. He had the power, as co-publisher with Thomas Bedingfield and Thomas Marshe to give the translation of Cardanus Comforte its “Cum Privilegio“. And, as we shall see, the permission was also granted for the 1576 revised edition as well.

Not to put too fine a point on this, but why Edward de Vere’s enthusiasm over the printing of this particular book, one that was officially sanctioned by the Crown? At the very least, the translation passed muster as a translation; which testifies to both de Vere’s probable supervision of the translation as well as to his knowledge of Latin. As well, is Cardanus Comforte truly about the contents within the plaintext, or is it about something else. Since de Vere’s is the only name in print on the frontispiece (“the right honorable the Earle of Oxenforde”), is there a hidden agenda, a hidden message to be had? Is this frontispiece really about Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxenford?

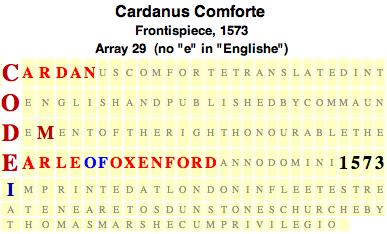

The following two arrays (Figures 1 and 3) are in the category of stretching things a bit. ‘Torturing the plaintext’ as I like to call it. I was able to find only a single array in the 1573 plaintext, given the absolute spelling presented. The question in my mind was in regard to the “Cum Privilegio” phrase:

Fig. 1a

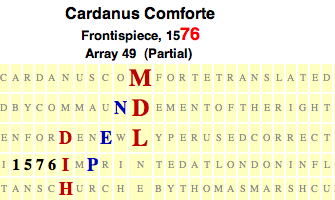

A diminutive for “Elizabeth” is “Beth”, another being “Bess”. The letter-string makes sense: the volume was printed with permission of Elizabeth I, Queen of England. However, satellite support for Fig. 1a above (with respect to permission granted by Elizabeth I for the 1576 revised printing of Cardanus Comforte) appears to support Vere’s contribution (s) to the translation (Fig. 1b below) as “MDL” are the Roman numerals for 1550, the alleged and probable date of Oxford’s birth. The original volume was written by Cardano in Latin. Thus, the Latin MDL for 1550 mirrors the associations of “Beth’s” continuing and implied legal permission (3 years later) for the second printing (cum privilegio) as well as her involvement with it’s production and association with de Vere’s date of birth. And, as we shall soon see, the connections this work has with Henry Wriothesley and the use of codes as a method of encoding private correspondence:

Fig. 1b

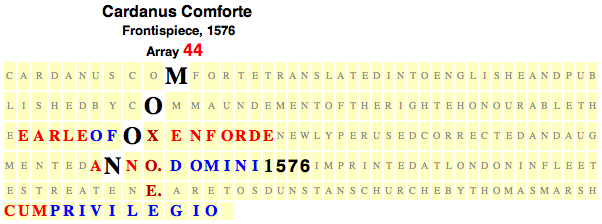

By the time of the 1576 “newly perused, corrected and augmented” publication of Cardanus Comforte, Elizabeth was rapidly becoming identified with the powers of the moon, and was often compared to the mythological deity of Artemis (Greek) or Diana, her Roman equivalent. This deity was the twin sister of Apollo, was associated with the love of the hunt, the forests and hills, stags, boars, and virginity. To many poets and playwrights of the latter part of the sixteenth century, the cult of Diana was a pronounced subject matter as a means of honoring and praising Queen Elizabeth. Sir Walter Raleigh became promoted the latter comparison with the attributes associated with Diana and the ‘cult of the moon’. An accomplished poet, Raleigh wrote what many scholars refer to as a poem, never published in his lifetime, entitled The Ocean to Cynthia, an elegy written in praise of Elizabeth I. There is no consensus as to the date of the poem’s writing, but scholars believe it was written before the death of Elizabeth, and may have been a verse of as much as 15,000 lines. “Cynthia” is another name for Diana (Artemis). The diagonal letter-string “MOON” in Array 44 in the 1576 frontispiece above not only reinforces Elizabeth’s involvement with Cardanus Comforte (i.e., with her attributional name, “moon”), but curiously is linked to the content of Cardanus (in my theory) to the known fact that Raleigh, as well as having been an explorer, writer, poet, aristocrat, and soldier, was also a spy. Codes and ciphers were a mainstay of Elizabethan spies. It is unlikely, therefore, Raleigh would not have known about encryption.

We are dealing with codes. Girolamo Cardano was interested in encoding hidden messages within the plaintexts of letters, correspondences, and developed a method for doing this (used widely at the time) called the Cardano Grille. Unlike an equidistant letter sequence, which has necessary sequential order, the Cardano Grille has no regular pattern. A cardboard overlay with cut-outs was used to reveal words and letters from a plaintext that spelled out a concealed message. Both sender and receiver had to have the same overlay to encode and reveal the hidden message. Again, the sender and receiver of an ELS only had to use the same method of encryption-decryption as well as knowing in advance what keyword (s) to look for. The point is that Cardano had interest for de Vere, both for his ideas on encrypting hidden messages, as well as (I suspect, since punning-number-play was one of his many literary devices, or ‘inventions”, if you will) his developing use of what was most likely de Vere’s own modification of the Cardano Grille. In fact, Edward de Vere’s use of the equidistant letter sequence (ELS) predates his use of it the work presently under discussion, in both the Sonnets and the plays, by several years. I will go into greater detail about this when discussing de Vere’s personal poetry contained in the Paradyse of Daynty Devises (1576).

Silent Thought

Cardanus Comforte Frontispiece, 1573:

Cardanus Comforte Frontispiece, 1576:

Having spent several years reading Shakespeare in the original printed spelling, I noticed a spelling not familiar to me in printed versions of any of his work: “Englishe”, with an “e”. A search for word presence and frequency use, provided the University of Chicago Library, prepared by Charlton Hinman and published by the Oxford Test Archive (not including Pericles, Prince of Tyre and Two Noble Kinsman) returned no spellings used for “Englishe“. 150 plus spellings of “English”, however are reported. Again, a search for “Englishe” in the concordance of the Internet Shakespeare Editions reported no use of the word “English” or “Englishe” at all in the Sonnets. A guide line, or suggestion, in cryptological studies is to suspect unusual spellings in a given plaintext. “Englishe” definitely satisfies this criterion.

My speculation is that a person (s) “in the know” at the time of the frontispiece publication (unlike a modern reader) would have noticed this. And since we are dealing with codes, I decided to eliminate the “e” from the plaintext. I figured making a “correction” in the spelling of a word in a plaintext might be worthwhile, as this might have been what the encrypter wanted a receiver to do. I assumed that perhaps the presence of the “e” was a clever cue alerting an astute reader (who was in “the know about coding and hidden messages) to the presence of a code in the frontispiece.

I removed the “e” and found the following in Array 29:

Fig. 3

The presence of “CODE” in its location, especially when it connects the “C” with “Cardan” and the “E” with “Earle”, to me, goes beyond chance. However, my argument hangs on a shaky premise. Despite that, eliminating the “e” for the reasons I did, and immediately finding the cluster above, is stunning to see.

The first 17 words in both plaintexts of the frontispieces of Cardanus Comforte, 1573 and 1576:

One striking feature of the plaintext is that the word “Oxenford” is the 17th word in the frontispiece. This is independent of the “e“. The word count remains the same. This is either coincidence or not. Deliberate or a chance occurrence?

The frontispiece of the revised second edition of Cardanus Comforte adds five words between “Oxenforde” (now with an “e”) and “Anno Domini 1576”. “Oxenforde” remains as the 17th word in the plaintext, and the last two words are still Cum Privilegio. What has changed, however, is the clarity of the reason why the first edition was printed in the first place, and is emphasized by what may be considered the genesis (or the continuation) of the conspiracy to keep concealed Edward de Vere’s intentions with his future writing.

I believe the year 1576 marks a profound change in both the attitude of de Vere, as well as a deeper reason for keeping his name hidden from the public. I should say ‘deeper reasons’, however, for there are several that emerge and play a dominant role in the content (perhaps even pretext) of and the subsequent turning to encryption to place this information throughout the plaintexts of the Sonnets and the plays. Furthermore, it must be remembered that the first appearance of the name “Shakespeare” was in the dedication to the poem, Venus and Adonis, in 1593. The dedication was to Henry Wriothesley, and was signed by “William Shakespeare”:

Many believe Henry Wriothesely, as previously mentioned, was the child of Queen Elizabeth and Edward de Vere. The date of his birth was 1573. This date has a further bearing (besides in the discussion of the Cardanus frontispiece above), in that it brings into focus one of the reasons for the printing of a second edition of Cardanus Comforte. Edward de Vere believed he was the next heir to the throne of England upon the death of Queen Elizabeth, and that their son Henry was therefore also heir to the throne. When Elizabeth early on refused to honor this succession, de Vere’s bitterness gave birth to one of the strongest and most pronounced motifs in his writing, and encryption became his most valuable tool. Once again I turn to what may be “coincidence“: Edward de Vere, as a writer, disappears in 1576; Shakespeare appears in writing for the first time in 1593:

1576 to 1593 = 17 years

In 1573, Sir Francis Walsingham continued his meteoric rise to power at Court. He became a privy councillor (advisor to the Queen). Five years earlier, in 1568, Walsingham worked with and was trained by William Cecil, Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, and arguably the most power person in government. In fact, many historians consider William Cecil to have been the real success behind Elizabeth’s reign. Under the tutelege of Cecil, Walsingham began to develop the first organized foreign espionage service in England. He developed a systemized method of training his spies, all designed for domestic intelligence gathering, but primarily to protect Elizabeth from her many foreign enemies. Walsingham quickly rose to become Elizabeth’s prime advisor.

Much of Walsingham’s energy focused on preventing a resurgence of Catholicism in England after the death of Mary I in 1588. England was surrounded by catholic nations, and catholic sympathizers and conspirators were fomenting disruption. Walsingham sanctioned the use of torture to extract confessions from many alleged conspirators, and from catholic priests in particular.

The focus of my interest is in codes as it relates to the Shakespeare canon. It is with this mind that the continuing development of cryptology under Walsingham must be emphasized. This development included some of the most brilliant minds in the history of encryption and decryption in any nation’s history. Walsingham hired the best that could be found. Foremost was the cryptographer and forgerer Thomas Phelippes. One of his Crown services was to decode letters sent by alleged conspirators against Elizabeth, and is most known for his part in the entrapment of Mary , Queen of Scots (Mary I of Scotland) by modifying an intercepted letter written to Mary, implicating her in a plot to overthrow Elizabeth by force (known as The Babington Plot). The upshot of all this was that Babington, a former jailer of Mary, Queen of Scots when she was jailed for suspected treason against Elizabeth, was intensely watched by Walshingham’s secret agents. When a series of letters were intercepted, Thomas Phelippes added an incriminating postscript to one of them (known as the “bloody letter”), which asked Babington for the names of the conspirators. The postscript, of course, was a false addendum, but was the letter incriminating Mary for treason; for which she was found guilty at trial, and was subsequently executed, by beheading, at Fotheringhay Castle, England, on Feburary 8, 1587.

Fragment of “the bloody letter” incriminating Mary, Queen of Scots, with Phelippes postscript

Edward de Vere was one of the jurors at Mary’s trial. A trained spy and master of codes, taught by Walsingham and William Cecil, Lord Burghley, it is unlikely he did not know about Walsingham’s manipulation of Mary’s letter to Babington, ensuring her conviction and execution. The pressure on the jurors (all appointed by Elizabeth) to find Mary guilty of treason was considerable.

Elizabeth was under tremendous pressure as well. Speculation as to what still remains a paucity of historical documentation of Elizabeth’s reasoning process during this time (keeping in mind nearly four months had taken place since October, 1586, when Mary was convicted and sentenced to death and Elizabeth’s final signing of Mary’s death warrant in February, 1587), includes (not an exhaustive list): 1) the ire of Catholic nations sympathetic to Mary was building. Elizabeth faced possible war over this, as well as internal strife at the national level. A crisis was unavoidable and had to be resolved with considerable skill and cunning. 2) Walsingham and Lord Burghley wanted Mary’s conviction and execution, an attitude unlikely to have gone unnoticed by Elizabeth, and possibly shared by her. 3) As already stated, Mary’s death knell was the altered substitution cipher-letter cryptologically manipulated by Walsingham ‘proving’ Mary’s guilt to the jury. 4) At this point, the cat was out of the bag and well-known. One anointed queen wished the assassination of another anointed queen. 5) Elizabeth did not want to set a precedent by ordering the death of another head of State as this would set a dangerous precedent. 6) Assassinating Mary would infuriate Catholics and Catholic nations, giving them good reason (particularly France and Spain) to declare war against England. 7) In historical hindsight it appears credible Elizabeth was perhaps less concerned with having her own cousin put to death than she was with not appearing to have done so. If this is so, then appearing to be ambivalent about not signing Mary’s death warrant for three and one-half to four months can be seen as political cunning. Delay could easily be seen as Elizabeth’s tacit permission to murder Mary’s before a public execution could be carried out (echoing Henry II’s infamous sentence when he wanted Thomas a Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury out of the way: “Will no one rid me of this mdddlesome priest?”) In this way, Elizabeth’s delay (like Henry II’s utterance, both ambiguous and explicit) might appear as being the actions of conscience rather than of malevolence. 8) There is evidence Elizabeth sent a request to Mary’s personal jailor (Sir Amyas Paulet, Knight) at Fotheringay Castle suggesting Mary be secretly murdered. The benefit of this to Mary would be less suffering and humiliation than being a public spectacle, and would make Elizabeth’s delays in signing Mary’s death warrant be a demonstration of mercy, as well as warding off, or at least postponing, a war with France and Spain, and internal strife in England. 9) It is alleged that after the beheading of Mary, Elizabeth stated she gave specific orders not to deliver Mary’s signed death warrant until she gave permission to do so. However, the execution took place before she was told it was to take place. Elizabeth was furious about this deception. On the one hand, this made her appear more of a victim of her counsellors than a party to a clever and cunning way of not taking public and international blame for Mary’s death, as well as eliminating immediate threats to her person and nation.

Speculation aside, what historical documents that do exist regarding the trial and exection of Mary, Queen of Scots, all agree that: 1) Elizabeth delayed of the signing of Mary’s death warrant from October, 1586 to February, 1587; 2) When she finally signed the warrant, she claimed she ordered it not be be delivered; 3) this ‘alleged’ order was ignored by Sir Francis Walsingham and Lord Burghley, both of whom hurriedly prepared for Mary’s execution and carried it out before first telling Elizabeth (although this, as well, may have just seemed to be the case to throw blame away from Elizabeth. The consequences of telling or not telling Elizabeth, though, were the same: Mary would be dead, and Elizabeth would not be seen as a murderer of a queen annointed by God.); and 4) that Elizabeth was furious at the deception.

Think about this for a moment: what is wrong with this picture? Elizabeth was one of the most politically successful monarchs in any nation’s history. Granted, Walsingham and Burghley had a wide berth in their respective delegated powers, but they were not democratically elected officials. The were a part of the glue in a dictatorship, not a democracy. Why would they demonstrate such defiance (sedition, more accurately) by: 1) manipulating a letter, resulting in the conviction and sentence of death of an annointed queen, knowing full well Elizabeth would take primary responsibility for Mary’s execution. 2) this was tantamount to defying their queen, incurring her wrath, thus risking their lives; 3) going behind Elizabeth’s back and executing an annointed queen without official permission? Why would they have done this? For the good of Queen and country?

They likely behaved as they did because the entire process was rigged from beginning to end. In an age of some of the most stunning drama ever written and performed, the Trial and Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots is a case of life imitating art.

What does this have to do with Edward de Vere? Was this drama possibly, perhaps probably, assisted by the man most able to create such a scenario? A drama rivallng if not surpassing any plot in any Shakespeare play, conceived and carried out in such detail, and with such a successful outcome? Yes and No. “Assisted” yes, but not planned from the beginning. I believe Oxford was sympathetic to Mary, learned of Walsingham’s treachery with Mary’s letter, and told Elizabeth what was transpiring. In true Shakespearean irony, either he was doing the right thing by Mary in telling Elizabeth, or when he did so, he was told by Elizabeth what was really going on. I do not believe it was de Vere’s brain child that false evidence be planted to incriminate Mary, but I do believe it is likely he was aware that whatever Elizabeth had chosen to do, could not be stopped on the grounds of moral appeal, and that if he were to go over Elizabeth’s head, everyone, including the nation, would pay a horrible price. Oxford could defy with impunity powerful men such as Walsingham and Burghley where others could not have done so, as he had done just this, many times, from the early days of his wardship under Elizabeth. But outright defiance in the matter of Mary, bringing State wrong-doing out in the open for the public and nations to see? Thereby shaming Queen Elizabeth and England? No. Whistle-blowing was likely not an option.

The major point of the above is that de Vere knew what was taking place. This gave him considerable power: he could say, “I know what you have done and are doing. I find myself a co-conspirator in this, and choose to be silent. So, we are all beholden to each other. Therefore, you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.” This is yet another reason for anonymity in his present and future writing, and a strong motivator (self-survival) for his choice to code information where the plaintext of what he wrote would conceal ciphertexts pointing to the behavior and character of others. If Hamlet is de Vere’s autobiography, as it is frequently claimed, then the major players in what “seems” to be fictional characters are really the names of the major players in the court of Elizabeth, including herself. Beginning after the trial and execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, de Vere, as a writer, virtually disappears and Shakespeare’s writing begins. As does the use of codes to support what conjecture hints at.

[ For more on Edward de Vere’s vote of ‘Guilty’, thereby condemning Mary to death, click HERE. ]

As we shall see, Edward de Vere had always been protected from the consequences of his behavior: from the killing of an undercook in a fencing ‘accident’ when he was 17, to his riotous squandering of money. Cecil, Lord Burghley, mopped up after him as can be seen in some of his letters to Cecil, entailing what amounts to constant and virtual begging for funds from Cecil in order to pay off his creditors. And, of course, who else could authorize these funds to be given to de Vere? Although Cecil was in charge of the wards of the Court (and de Vere was one of them from the age of twelve until his alleged death in 1604), Elizabeth had to have given permission (“commaundement “) for this. What intrigues me, however, is for what reason (s) was Elizabeth so protective of a person so seemingly irresponsible?

I suspect Edward de Vere knew of Elizabeth’s doubts about executing her own cousin, as well as having been privy to the creation of the incriminating letter by Thomas Phelippes, as instructed by Sir Francis Walsingham. My guess is that de Vere refused to take part in this deception, going so far as to vote against Mary’s conviction and beheading. If I am correct, de Vere was, in all probability, duty as well as morally bound to tell Elizabeth about the false postscript. De Vere was a Crown spy. There are no written documents of the discussions between Walsingham and others regarding their conspiracy to falsely accuse Mary of treason. Perhaps de Vere told Elizabeth before or after the execution. Perhaps not. After all, Walshingham’s power and control of State and Crown security hinged on remaining credible and trusted by Elizabeth. Perhaps Elizabeth was convinced by him that Mary had to go as her being alive remained a continual Catholic threat to her, and therefore to England. She may have caved in and consented to the deception. But if she wasn’t told, De Vere would still have been a liability to Walsingham at this point, and most likely not easily persuaded to keep silent without some serious intervention. It would make sense, in all this skullduggery, for Walsingham to say to de Vere that he would have him killed (along with his family) if he said anything to anyone. Walsingham doubtless knew of the protective status given him by Elizabeth (Cecil would have made sure of this), and would not breach this condition unless absolutely necessary to do so. This meant he, himself, was threatened in a most horrible way with execution by Elizabeth for his part in the death of Mary. For his part, so accused by Elizabeth, he could publicly have his bowels cut out and burned before his eyes while he was still alive, then be executed. Knowing this, he would be more than motivated to protect himself in this regard. Secrecy and keeping things hidden was life and death for all involved.

By 1587 and the trial of Mary, de Vere would have been exceptionally well-trained for espionage, perhaps more so than Walsingham himself. After all, Sir Francis Bacon was a ward in the house of Cecil along with de Vere, wrote a brilliant book about codes and ciphers, and had William Cecil train him as well in the use and methods of cryptology. As to Edward de Vere, he was finely honed to be perhaps more qualified to use codes and ciphers than anyone in England, or on the Continent, for that matter. Hence de Vere’s obsession with both word and number-play in his writing.

All this brings us back to Cardano and the Frontispieces of 1573 and 1576. We have now seen (or have reason to believe) how de Vere could easily have been recruited by William Cecil into the world of espionage. De Vere’s maternal uncle, Arthur Golding, was one of de Vere’s private tutors, and enlisted his help in translating from Latin, Ovid’s Metamorphoses while Edward was still in his teens, and Golding (as well as all de Vere’s tutors) could vouch for de Vere’s exceptional intelligence, keen wit and talents for everything from competence in several languages and musical ability, to those of an accomplished athlete. To believe Cecil would not enlist the brain-power of de Vere (as well as that of Francis Bacon) is to believe the extremely unlikely. At the same time, as well, we are beginning to see that young de Vere’s knowledge of the machinations of Court life and intrigue is building, along with many secrets about key individuals in this protected sphere, that added to the protective status he already had from Elizabeth. De Vere was always seen as a loose canon. His impaired judgement as well as his riotous and irresponsible living contributed to his never being given a position of responsibility in Elizabeth’s government, despite his frequent requests to Elizabeth to be given one. But his understanding of the personalities of the Court (as well as a great understanding of human behavior in general), was quickly developing. As early as 1573 we see his life being keenly sculpted for the life of a great poet and playwright. He was already quite a court favorite. However, he was also earning a negative reputation as early as 1573. However, on or about the 17th or 18th of March, 1575, his life takes a dramatic turn for the worse (in his opinion), the consequences of which would last for the rest of his life.

” . . . my name receives a brand . . . “

In a letter (this and all letters referred to are from the known set in existence to be written in de Vere’s own hand) to Lord Burghley (William Cecil, his wife’s father), composed and dated by de Vere as “17 -18 March 1575“, he writes the following in his opening lines (ironically indicating the initial first few lines of the letter were written on the 17th):

“My lord yowre letters haue made me a glad man, for thes last haue put me in asseurance of that good fortune whiche yowre former mentioned doughtfullye. I thank god therfore, withe yowre Lordship that it hathe pleased him to make me a father wher yowre Lordship is a grandfather. and if it be a boij I shall lekwise be the partaker withe yow in a greater contentation. But therby to take an occasion too [=to] returne I am far of [=off] from that opinion, for now it hathe pleased god to giue me a sune of myne owne (as I hope it is) mithink [=methinks] I haue the better occasion to trauell, sithe whatsoeuer becommethe of me, I leue behind me on [=one] to supplie my dutie and seruice either to my prince or els my contrie.” (color emphasis mine).

There has been some speculation as to the meaning of the first line, with respect to: “yowre former mentioned doughtfullye.” The reference, of course, is to the last few letters received from Lord Burghley. the “haue” (have) is plural and refers to more than one letter; expressing doubts, I surmise, about whether Anne is definitely with child. Anne Cecil, Burghley’s daughter, married Edward de Vere on December 16, 1571. The marriage was childless up to this point, and the expectation of a child doubtless thrilled both de Vere and Burghley, especially if were to be a boy (boij). A boy would provide Edward a male heir, simultaneously making Lord Burghley the grandfather of the Eighteenth Earl of Oxford. What happened next is a matter of deductive history, rather than outright document-stated fact.

The next surviving letter in the historical record from de Vere to Burghley shows the date, September 24, 1575. He talks about his “dispaire” at not receiving correspondence from Burghley, but finally receives five letters, two from Burghley and three from himself written at various times during the summer that did not get through to Vere due to mail not being able to progress to England from the Continent on account of roads being closed as a measure of containing the spread of the plague. The March correspondence to Burghley was written in Paris. Now in Venice, having just received two letters from his father-in-law and three of his own returned to him, we can imagine what must have been great anticipation about the birth of his first child. He further talks about his own previous illness, his debts, and other matters, including responding to some of the questions asked by Burghley in the newly received letters. At the closing of his correspondence, de Vere writes:

” [T]hus thankinge yowre Lordship for yowre good newes of my wiues deliuerie, I recommend my self vnto yowre fauoure and allthought [=although] I write for a few months more yet thowght [=though] I haue them so it may fall ought I will shorten them my self. written this 24h of September by yowre Lordships to command.(signed) Edward Oxenford”.

What is striking to me is the lack of curiosity about the gender of his child. This apparent lack of curiosity may not be a lack, but rather reflect what we do not historically have: the Burghley letter (s) themselves. That notwithstanding, what does seem apparent in his September 24th letter is the absence of inquiry as to the gender of his child. For all we know, a letter from Burghley may have been on its way to de Vere, yet de Vere says nothing. It would therefore seem Burghley either omitted this pertinent fact, or flat-out does not say. De Vere’s concerns in his return reply reflect his ill health, not liking Italy, his debts, and so on, but nothing about his wife, how she is, how the child is, or what really does concern him: the gender of his child: is it a boy or a girl? He mentions the plague, but not whether the plague is presently in England. That we are aware of, at any rate. What we do know, however, is that the historical record is silent in this regard. For all we know, multiple letters on both sides (Burghley to Vere and vice versa) may have taken place. Burghley could have told Vere his child was a girl (which she was). There might have been detailed correspondence between the two.

What is remarkable, furthermore, is that de Vere, with all his contacts, from Elizabeth herself to others in the Court, the historical record does not reflect de Vere having written to anyone about Anne, her welfare, the welfare of the child, or as to the gender of his child. Then again, we have no documents to say that he did not write many letters to several of his friends — at this point in time. For all we know, he may have done all this. Until more documents emerge sometime in the future, we shall have to remain in the dark.

On November 27, Oxford writes a short note to Burghley concerning the sales of his lands, and closes with: ” thus recommendinge my self vnto yowre Lordship againe, and to my Ladie yowre wife, withe mine [=my wife (Anne)], I leaue further to troble yowre Lordship from Padoua. the 27h of Nouember.” Again, no inquiry as to the health of his wife and child, nor as to the gender of the child. The letter reads like a business memorandum.

Still in Italy, Oxford writes a comparatively long letter to Burghley on the 3rd of January, 1576. Consisting of nearly 950 words, the entirety of the letter is business related, and ends thus: “Yowre Lordshipes to commande duringe lyfe. the 3o of Ianuarie. from Siena.” It’s clear de Vere spends a lot of time corresponding with others than Burghley. A lot of concerns are expressed, but again, nothing about his wife and child, their welfare, or the gender of their child. He doesn’t refer to any correspondence between his wife and himself; their is no documentary evidence during this time they wrote each other. Two months have passed, according to the written trail of Burghley-Vere letters, and we have the total absence of questions on Vere’s part about his wife and child, nor about the child’s gender.

Historical accounts of what happened between the January letter and the letter to Burghley of April 27, 1576 are unclear as to what occurred with regard to the events leading up to it . Speculation holds that de Vere had been refusing to lay with Anne since 1572, and that at one time, Oxford presumably ordered one of his servants to prevent Anne from access to Oxford’s sleeping chambers. Another account says Oxford did not sleep with his wife until October of 1574. And still another claim is that Queen Elizabeth said de Vere (in her presence) stated the last time he had slept with his wife was at Hampton Court in October (1574); and therefore, if Anne gave birth on July 2, the child could not be his. What does seem to be the case is that de Vere is doing the math, beginning his gestation calculations when he believes he last had relations with Lady Anne. Furthermore, sometime in April of 1576, while he was still in Paris, he was told scandalous Court gossip had it that the child was not his, and that he had been cuckolded.

Controlled rage at this most likely loss of his good name is reflected in his letter to Burghley, written on 27, April, 1576. The contents of the letter are doubtless sensitive; therefore, outright statements regarding them, Vere writes, will have to wait until they can discuss the matter in private, presumably as a control against the letter being intercepted for Burghley can receive it. The entire letter is quoted below.

Fig. 6

What is striking about the April letter is its tone. Lord Burghley, second only to the Queen, was the most powerful person in Tudor England. His control was considerable and virtually complete. He was Elizabeth’s premier advisor, head of a secret espionage organization which was arguably the most competent in England and on the Continent, and yet appears, at least on paper, to being bullied by an Earle and ward of the court (conditions Vere would not escape for the rest of his life), and in a position to assist in de Vere’s constant insolvency. Yet the tone of de Vere’s writing is both pretentiously subservient and flagrantly arrogant and entitled. He dictates terms to Burghley, excoriates his judgment, and essentially demands a conference with him when he soon returns to England. Burghley, up to this point, had consistently bailed out the young and irresponsible Earle out of debt. There is no doubt Oxford was protected by Burghley at every turn, yet de Vere appears to be in control. The question then becomes, if Burghley is Oxford’s often exasperated protector, who is demanding he spends his time this way, and why is he so doing? And if Burghley is protecting Oxford, then who is protecting Oxford from Burghley? Why does de Vere have what appears to be unmistakeable power? What is it he has that allows him to seemingly use his own wife as hostage to what he wishes? Simply that Burghley wants a grandson who will inherit a powerful earldom and thereby further ennoble his own name and House, or is there something else Vere has that those with more power and control fear? And is any or all of this reflected in his writing?

In the preceding three and one-half months prior to the writing of his April 27 letter, de Vere has been doing the math. Whatever the actual truth of the matter, de Vere believed he was not the father of the child, Elizabeth, born July 2, 1575. He would remain estranged from Anne for the next five years. They were to reconcile in 1581, but the damage done to de Vere’s psyche was considerable. His disillusion with human relations and behavior is densely reflected throughout a lifetime of written work.

Present day knowledge of human gestation was not available to Elizabethan medicine. What medicine and the common Elizabethan understood, however, was that from conception (or the awareness of it, verified by a physician) to delivery was about nine months, or 270 days. It was known at the time there was a range in human gestation. Premature and overdue births were understandably a part of what still remains an educated guess regarding conception and birth.

Today, human gestation data is continually collected and analysed. Obstetrical and gynecological analyses are category-specific. What is meant by a normal pregnancy is medically referred to as “uncomplicated human gestation”. This descriptor eliminates gestations with “known obstetric complications, maternal diseases, or unreliable menstrual histories”. Modern medicine predicts birth on the basis of a range. At present, the median length of gestatation from assumed ovulation to delivery is longer for the first pregnancy (primiparas) is predictably longer on average (about 5 days) than women who have been pregnant two or more times (multiparas). Studies indicate when predicting the birth of a child, one must take into consideration the first day of the last menses, then add 15 days for the first pregnancy and 10 for second (and thereafter) pregnancies. Then count 269 to 274, whichever may apply, to arrive at a possible delivery date. Therefore, the Elizabethan educated guess at a delivery date corresponding to a nine month period aligns with modern day medical predictions of conception-to-delivery estimations when telling a woman when she is most likely to deliver.

Applying what medicine now knows to be a reasonable and reliable conception-to-delivery calculation, albeit within a range, our present-day estimations hold for the Elizabethan woman as well. We have no documentation on the medical history of Anne de Vere, but we can say modern day estimations of the lengths of pregnancies apply to her. Within reason (even taking into account a non-typical pregancy), Anne could easily have delivered in July if Oxford’s memory of only having relations with her occurred sometime in early October. However, if his memory was not accurate, and he did have intercourse with Anne as late as mid-November, then an overdue baby could have been delivered in the first few days of September, 1575. But Burghley recorded July 2 as the birthdate of his newly born granddaughter, Elizabeth de Vere. Furthermore, to complicate matters, speculation has it that Oxford’s servant, Rowland Yorke, met him in Paris in March, 1576 and tells Oxford that Burghley misrepresented the July birth date, changing it thus from September to July, as well as informing Oxford of the enormity of Court gossip saying he, Oxford, was a cuckold, and thereby a laughing-stock. And when he arrived back in England, his cousin, Lord Henry Howard, 1st. Earl of Northampton, fueled the issue of Anne’s infidelity by saying Anne had been unfaithful. History says Henry had problematic character issues, may have been partially (or mostly) responsible for the ruination of his own brother, and was intensely disliked by Burghley. Suspicions, at least on my part, are that Henry had an axe to grind with him, hence setting up what today is the game of “let’s watch you and him fight.” The historical record of his dealings with others points to the behavior of a sociopath. At any rate, Oxford thereafter accuses Anne of adultery, and his five-year estrangement with her begins. For my part, I strongly believe Anne to have been innocent of all accusations of adultery, and will address this in reasonable detail later, along with letter-strings as support.

We know nothing of Anne’s sexual behavior before or during her marriage to Oxford. We know he took as credible, reports from others that Anne was an adulteress. In de Vere’s letter to Burghley (dated July 13, 1576, and the last known letter Oxford wrote to him regarding the birth issue) in his own hand), de Vere reports in his opening sentence he talked about ‘issues’ with him, and refers to having talked with Queen Elizabeth as well; doubtless about Anne’s behavior amongst these issues, as well as referring to the Queen’s counsel regarding at least as to whether or not he (Vere) would allow Anne to be present at Court when he was there at the same time. Underscoring the comment about having discussed the issue about Anne’s situation to Burghley is worthwhile. Oxford is nothing if not skilled at pointing out to his father-in-law where the power really lies. The phrasing used in the opening sentence of the letter to him is a virtual scream that Burghley is out of the decision-making loop. Once again, just what it is de Vere has or knows that gives him this decidedly powerful control is not something history can say with certainty. Oxford concludes the letter (reproduced in full below) by again dictating terms to his powerful father-in-law, and with a certain amount of implied impunity.

Oxford’s July 13, 1576 letter written upon returning to England, from his temporary residence at Charing Cross, London:

“My verie good lord, yesterday, at yowre Lordships ernest request I had sume conference with yow abought yowre doughter, wherin for that her Magestie had so often moued me, and for that yow delt so ernestly withe me, to content as muche as I could, I dyd agre that yow myght bringe her to the court withe condition that she showld not come when I was present nor at any time to haue speche withe mee, and further that yowre Lordship showld not vrge farther in her cause. But now I vnderstand that yowr Lordship means this day to bringe her to the court and that yow mean afterward to prosecut the cause withe further hop [=hope]. Now if yowre Lordship shall doo so, then shall yow take more in hand then I haue or can promes yow. for alwayes I haue and will still prefer myne owne content before others. and obseruinge that wherin I may temper or moderat, for yowre sake I will doo most willingely. Wherfore I shall desire yowre Lordship not to take aduantage of my promes till yow haue giuen me sum honorable assurance by letter or word, of yowre performance of the condition which beinge obserued, I caud [=could?] yeld [=yield], as it is my dutie to her Magesties request, and beare withe yowre fatherly desire, towards her. otherwise, all that is done can stand to non effect. from my loginge at Charinge crosse. this morninge. Yowre Lordships to emploi”

(signed) Edward Oxenford

The ” . . . fable of the world . . . silently handled“

In all, there are six letters from Oxford to Burghley during Anne’s pregnancy-t0-delivery. Five are written during his period of absence from England. Three written in 1575: March 17th (Oxford acknowledges his wife’s pregnancy); September 24th (Oxford learns of Anne’s delivery in July); and November 27th ( substantively regarding business concerns as well as wishing Burghley’s wife and his own wife, well). And three written in 1576: two from the Continent: January 3rd (business concerns; no mention of his wife or newly born child or its gender); and April 27th (Oxford’s displeasure with Burghley’s handling of Anne’s pregnancy and delivery, and the Court’s response to it; i.e., how “the world reised suspitions openly, that withe priuate conference myght haue bene more silently handled”. The third and final letter (in the historical record) written on July 13th from Oxford’s temporary residence, “Charinge crosse”, requesting Burghley not to present Anne (who was living with her parents at the time) at Court when he (Oxford) is present at the same time she is. As previously mentioned, no surviving letter (s) in Oxford’s hand exists in the historical record, concerning the pregnancy-delivery question following the July 13, 1576 letter. The next letter written in his hand (analytically certified) was written on or about July 13, 1581, the year he reconciles with his wife.

Before returning to the 1576 revision of Cardanus Comforte, however, the change of tone present in Oxford’s six letters above from that of an obsequious soliciting of funds from Burghley to assuage his (Oxford’s) creditors, to that of tone-implied entitlement and arrogance toward his powerful and influential father-in-law, is necessary.

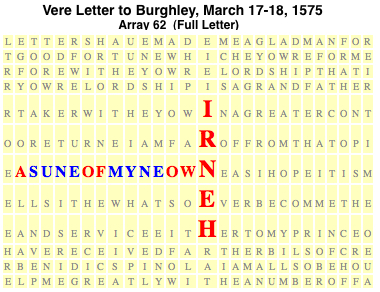

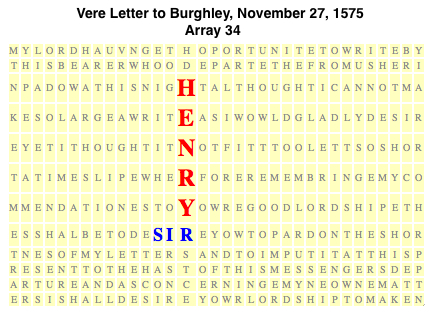

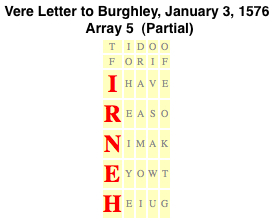

We know Burghley and Walsingham called the shots in the area of espionage. They both used and understood codes and ciphers, and doubtless both (at least Walsingham) trained de Vere and others to function as Crown spies on both travels abroad and at home. When I read the letters, I could not shake the feeling that some sort of veiled threat was somewhere within or between the lines. With this in mind, I arrayed all six to see if my hunch was correct, as well as to support my suspicions as to what the pre-dominant keyword might be; and that this keyword itself would be the threat behind the tone, one so strong as to leave Lord Burghley without doubt as to what this keyword meant to his power base, and to England itself. From my reading of the letters and the keyword I found in each and everyone of them, I concluded both my hunch and suspicions turned out to be warranted. I therefore decided to present each letter in chronological order, beginning with Oxford’s March 17, 1575 letter.

” . . . my Lord, I am too much i’th’ Sun.” (Hamlet, I.ii.247)

Fig. 7 (Pregnancy Letter)

Fig. 8 (Delivery Letter)

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11 (3rd Paragraph)

Figures 12 and 13

Fig. 14

Aug 10, 2014 @ 10:01:15

you are aware, are you not, that Giralomo Cardano was invited to England to examine King Edward VI … unfortunately for Cardano, his horoscopic prediction of the King spoke of his future marriage, which was delivered just after Edward’s death. Cardano died in 1576 … I think deVere might have visited him … he certainly had good cause

LikeLike